In many teams, error handling is treated as a minor technical detail a quick log and a generic 500 status. But as systems grow, that superficiality becomes costly: more debugging time, harder-to-trace incidents, and less confidence in production. Refactoring error handling is not just code cleanup; it’s designing the ability to understand the system when it fails.

Systems don't break when everything works; they break when something fails. Yet most architectures are designed for the happy path: the request arrives, logic runs, and the response leaves. The problem shows up when things go wrong: if errors lack structure, if there's no clear contract for status codes, and if logging isn't tied to metrics, the system becomes opaque and an opaque system doesn't scale. At Meetlabs, we understand that observability doesn't start in Datadog; it starts in how you define your errors.

When there's no clear error-handling strategy:

This creates something costlier than downtime: uncertainty, uncertainty slows the team down a system that doesn't explain why it fails forces you to investigate every incident as if it were the first time.

A well-designed error is more than a message it's a contract. It should answer, at minimum, three questions:

When errors are structured with internal codes, clear categories, and enriched context, the system begins to generate reusable information. That information feeds metrics, dashboards, and technical decisions. The result is simple: less time searching, more time fixing.

In Go applications, HTTP middleware and gRPC interceptors let you centralize error handling in a single place. This changes team dynamics. Developers no longer have to remember how to log or which status code to use the system defines it by default.

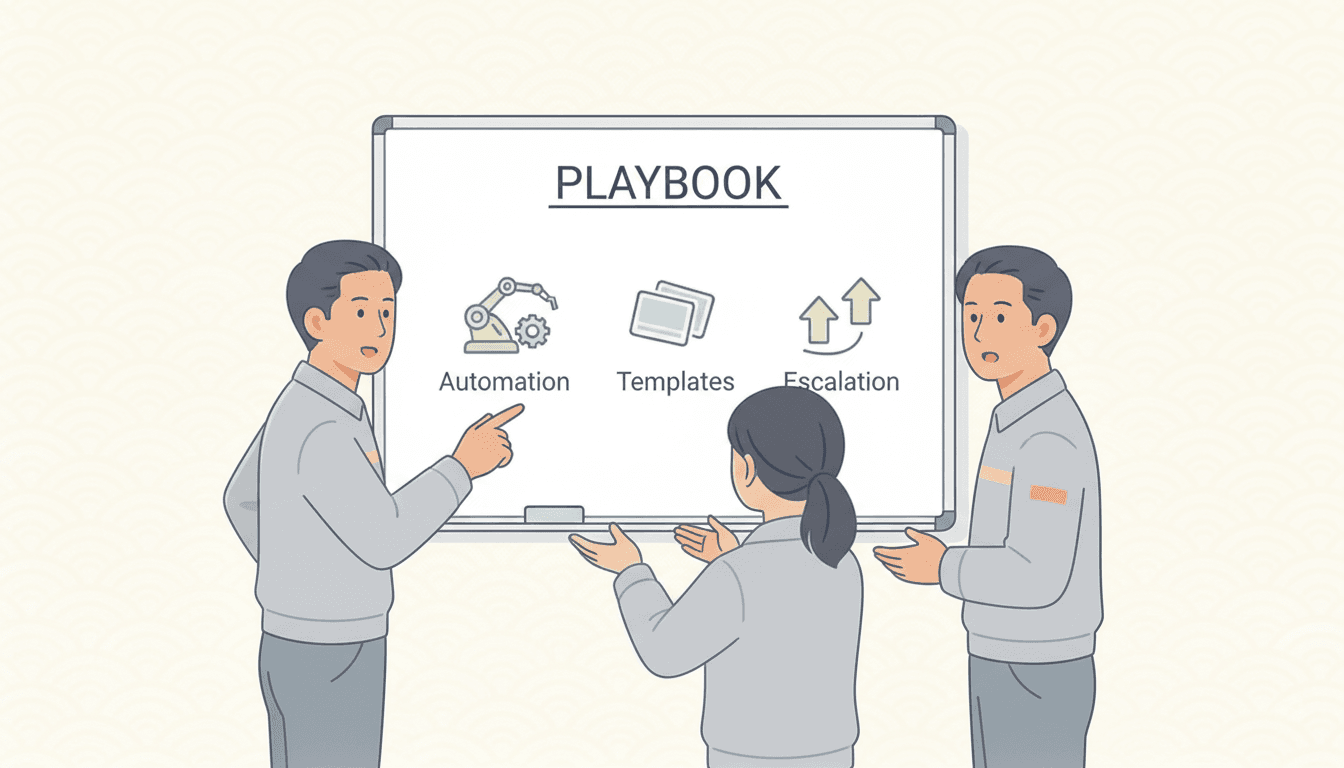

Centralizing error handling enables:

This is not just a technical improvement; it's an organizational one.

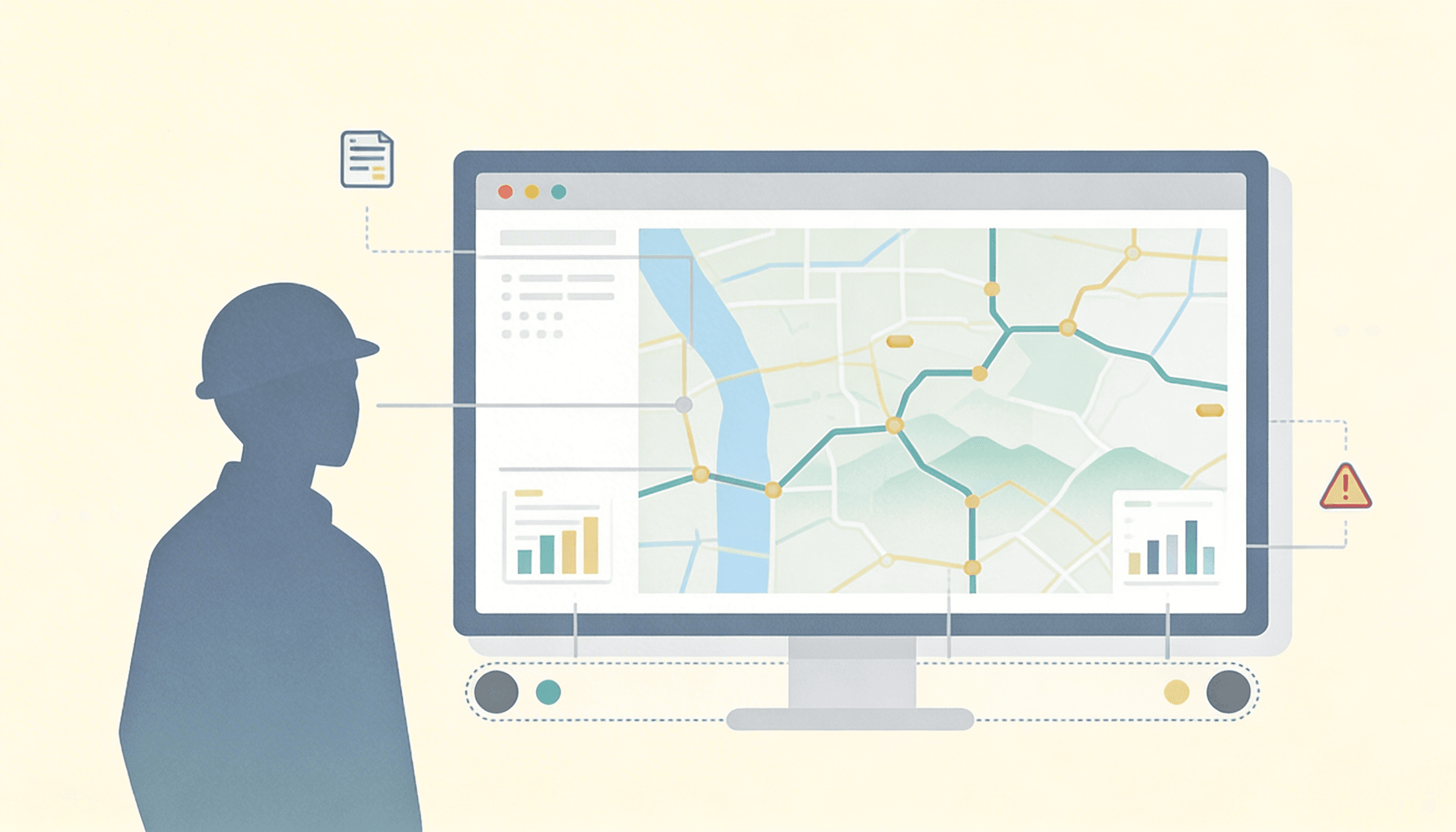

Tools like Datadog let you visualize metrics and logs in real time, but no tool can compensate for an opaque architecture. If errors are not categorized, codes are inconsistent, and context doesn't travel with the request, dashboards will only show symptoms, not causes. Real observability starts when the system is designed to be understood.

As a product grows:

If error handling is inconsistent, complexity grows exponentially. If standardized, complexity becomes manageable. A good error-handling system reduces friction, speeds onboarding, and enables decisions based on real failure data not intuition.

Error handling is not a secondary concern it is the architecture. Systems that scale are not those that fail less, but those that understand why they fail. When error handling is clear, structured, and observable, the organization gains something more valuable than uptime: sound judgment.